Resale platforms gain steam as they grapple with business model

Resale is certainly having a moment, but questions of long term profitability persist.

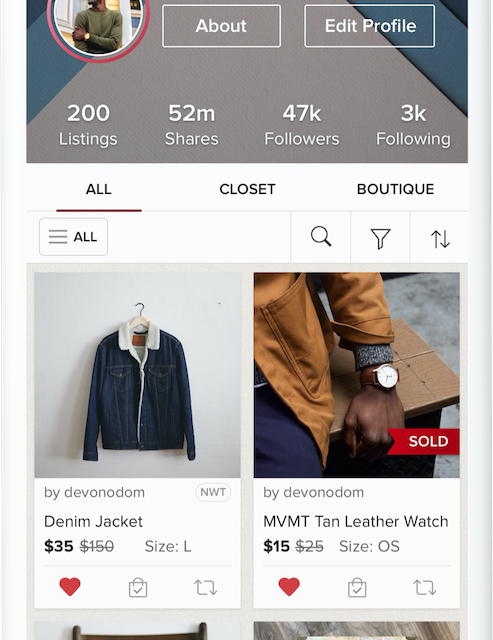

Thanks to the ample time for users to clean out their closets, resale platforms have experienced a surge this year. Peer to peer sites like Mercari and Poshmark — as well as wholesale-leaning services like The RealReal and Paris-based Vestiaire Collective — are gaining traction among both users as well as the designers they consign.

Currently, demand is at fever pitch. Poshmark — which currently has 60 million registered users as it prepares for an IPO — has a “sale made nearly every second,” CEO Manish Chandra told Modern Retail earlier this year. Growth has also evidently paid off for venture-backed Mercari, whose shares jumped by almost 25% since its last earnings. The startup’s fourth quarter earnings, released in August, showed it became profitable for a time during the quarter. Mercari U.S. achieved a monthly Gross merchandise value of $100 million, thanks to a 183% year-over-year growth.

Over at Vestiaire Collective, which raised nearly $65 million this past spring, “community interactions” between members experienced a 10x increase during the first few weeks of lockdown this spring. And according to the company’s semi-annual report from July, customer orders increased by 19% year over year in May.

Consignment platform ThredUp boasted its ability to “avoid the Covid retail slump,” according to its annual report released this summer. The platform saw an increased activity during lock-down, thanks to record site visitors in May; visitors spent 37% more time browsing compared to pre-pandemic figures.

Meanwhile, The RealReal’s latest earnings showed total revenue increasing by 11% year over year to $78.2 million, along with gross merchandise value jumping 15% to $257.6 million.

But as these companies grow, their exit strategies become more closely watched — especially as retailers look to invest in their own in-house resale program.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

A difficult model

Such high demand costs money. Right now, many second hand sales sites are subsidizing shipping in order to attract users, Forrester principal analyst Sucharita Kodali explained. Other companies, like ThredUp, rely on people sending in clothes, that then have to be sorted, uploaded and sold once again — such an infrastructure is expensive, to say the least. “I don’t know what the plan is for shifting the burden to sellers or buyers, that may be their biggest challenge,” she said.

But building these infrastructures isn’t cheap, especially during the pandemic’s boom. As The RealReal’s latest quarterly earnings showed, its net loss was $38.3 million. And despite achieving temporary profitability this year, Mercari’s global operating losses grew to $180 million, compared to $110 million during 2019’s fiscal year losses.

As Mercari U.S. CEO John Lagerling told Modern Retail recently, second hand sales sites have been building their infrastructure for years to be able to satisfy this demand.

Kodali noted that niche sites such as 1st Dibs, Chrono24 or GOAT — which sell pre-owned furniture, watches and sneakers, respectively — might work when it comes to building a sustainable business that doesn’t rely on the casual fashion seller. “Those price points are high and rely on collectors, so shipping isn’t an issue,” she said. “For mass products, it’s much much more difficult to have a long term play.”

Steven Schneider, chief operating officer at Worthy, a consumer-to-business luxury marketplace that specializes in diamonds, agreed. Though the company saw an initial slump during the early days of the coronavirus, it then saw double digit month-over-month growth since April. “Consumer intent to sell has gone up,” explained Schneider. He credits some social factors, such as the need for cash flow and divorce rates’ increase, as reasons for individual sellers’ decision to part with luxury jewelry at this time. “The divorced woman is one of our base customers,” he said.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

While declining to disclose Worthy’s profitability status, Schneider pointed to its category as an advantage that could assist it along the path to profitability “at some point.”

The other headwinds resale platforms face are brands building programs in-house. Kodali predicted that brands will most likely “own their resale in the future” in the way car makers like Porsche and BMW have come to dominate certified pre-owned. This includes brands’ ability to use local stores that can get their own used items authenticated.

Resale partnerships with brands have been on the rise even prior to coronavirus stay-at-home orders. In January, Rent the Runway announced its latest Nordstrom partnership, called RTR Revive, in which shoppers can Rent the Runway pieces at select Nordstrom locations. ThredUp also was growing its business-to-business service via partnerships with retailers like Gap, Macy’s and JCPenney, which focuses on selling ThredUp items at their stores (it just added Walmart as the latest partner). And after years of resistance to third party resale, Gucci struck up a partnership with The RealReal this month.

Meanwhile, some retailers and brands are still attempting to go at secondhand sales themselves. This month Levi’s announced its new buyback program, called Levi’s SecondHand, to capitalize on the denim brand’s popularity among vintage and thrift store shoppers. Separately from its Rent the Runway deal, in January Nordstrom began experimenting with a resale shop called See You Tomorrow. It also created a store-within-store at its new New York City flagship to go along with the consignment program.

Even so, both investors and founders believe that given the momentum, the economics will soon fall in place. “There is no question that you could build a model that achieves profitability,” Schneider concluded. “The customers are out there and the margins are big enough.”