DTC Briefing: Why churn rate isn’t always a good indicator of retention

This is the latest installment of the DTC Briefing, a weekly Modern Retail+ column about the biggest challenges and trends facing the volatile direct-to-consumer startup world. More from the series →

As acquiring customers becomes more difficult, retention is becoming a bigger topic of conversation among DTC executives.

More startups are reporting near-flat or declining DTC sales, as it has gotten more difficult to surpass the astronomical e-commerce growth rates reported in 2020 and 2021. In turn, more of them are talking up how well they are doing at retaining customers in order to paint a more positive picture. “While new customer acquisition was challenging in the first half of fiscal 2024, we’ve been very pleased with our customer retention this year, which is near all-time highs,” Bark CEO Matt Meeker said during the company’s third-quarter earnings call at the beginning of February.

But while there’s a lot of talk about what things DTC brands can do to improve retention — launching a loyalty program, sending personalized emails — there is less talk about how to effectively measure retention. And a new academic paper indicates that there are drawbacks to one of the most common metrics that DTC brands use to measure retention. In essence, the paper claims that churn rate — or, the percentage of customers lost over a given period of time — is a misleading way to measure retention. And, that looking at purchasing trends by customer cohort is a better way to measure the health of a brand’s customer base.

There’s implications here for both subscription and non-subscription based brands. This research underscores that for growing brands, declining churn rates isn’t necessarily an indicator of increasing customer loyalty. In fact, if they do interpret declining churn rate as a sign that they are finding product-market fit and increasing customer lifetime value, it could lead to faulty forecasts and overestimating how big they will grow to be in the future. Rather, looking at customer data on a cohort level could do a better job at indicating how well they are doing at retaining customers.

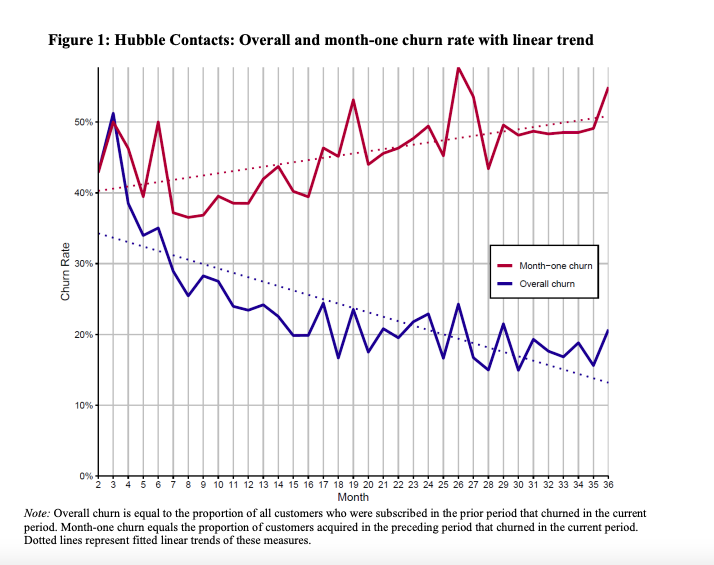

Called “The Declining Churn Fallacy Over the Product Lifecycle,” this paper analyzed the churn rates of 25 subscription-based brands over time, using data from Earnest Analytics. It finds that churn rate pretty much always declines over time, even as cohort-specific churn rates are increasing over time.

“You often see this in pitch decks for young companies, they always include this projection for what is going to happen in the future,” Dan McCarthy, an assistant professor of marketing at Emory University’s Goziueta School of Business, and one of the co-authors of the paper said. “Oftentimes, they will assume that retention is going to get better over time, that it is going to be one of the ways that they make more revenue — and usually the opposite is true.”

Essentially, what McCarthy’s paper found is that it is really hard for a brand to report anything but a declining churn rate. And, that’s not necessarily an indicator that a brand is doing a better job at retaining its customers.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

That’s largely due to something that McCarthy coins as the falling hazard effect. The probability of churn for a particular customer cohort tends to decline over time, as the mix of customers shifts towards those with a longer tenure.

Take a meal subscription service. If you look at the cohort of customers who sign up for a meal subscription service in any given month, a certain number of those customers are those who signed up simply because they had a promo code and wanted to get discounted meals for a month. Those customers are likely to cancel after the first month. Other customers might try out the service for a few months, and realize that, actually, they don’t like cooking intricate meals multiple times a week.

But, if you zoom out to, say, six months or 12 months later, the group of customers that have still stuck with that meal subscription service are those that are likely going to continue to stick with that service, because they have realized that the service is indeed a fit for them. Thus, the probability that that customer cohort is going to churn goes down each month. In turn, this drives the overall churn rate down, even if the churn rate for each cohort goes up each month.

One of the brands McCarthy and his co-authors studies is Hubble contacts. The paper looked at Hubble contacts’ monthly churn rate over its first three years in business, using a credit card panel dataset from Earnest Analytics. The authors found that even though Hubble’s overall churn rate fell by more than 50% over three years, the number of customers that churned within the first month increased from 40% to just over 50% over the first three years.

McCarthy said that the findings aren’t entirely surprising. In its early days, a DTC brand is more likely to acquire customers who are more passionate about the brand, or are attracted enough to the product and offering that they are willing to take a chance on an unknown startup. “If you are jumping on the bandwagon late, you are probably less likely to be passionate about a brand, and are more likely to churn,” McCarthy said.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

What it points to is simply that DTC brands — including those that offer a subscription service and those that don’t — simply need to be more aware of the limitations of churn rate, as well as how certain cohorts tend to behave.

Jai Dolwani is one marketer that advocates for brands doing cohort-based modeling to assess the health of their customer base. Dolwani, formerly the chief marketing officer at Winc, is now the founder of The Starters, a platform that helps brands find freelance e-commerce talent.

“If a company is declining because they’re not acquiring subscribers, blended churn rate is going to go down because the average age of their customers is significantly older,” Dolwani said. One metric he suggests companies instead look at is time-bound retention rate. With a time-bound retention rate, a company picks a certain point in time after a cohort was acquired– say, three months, six months, or 12 months — and use that as the basis of analysis, to look at data that’s not skewed by customers who churned early.

“You’re essentially looking like at a trended line over time,” Dolwani said. “And based on the time that you’re using — say, if you’re using one year or 12 month time-bound [retention rate] — then the latest data point that you’re gonna have is from a cohort that you acquired a year ago.”

He also suggests companies look at LTV using cohort-based forecasting. Shopify Analytics (so long as companies aren’t on the most basic plan) allows brands to pull cohort monthly revenue data. He’s outlined a template for how brands can do so. Brands can use this data to also look at things like: How does a cohort that was acquired in November behave compared to one that was acquired in July? Or, how do customers that were acquired during a heavy promotional month behave?

Ultimately, it points back to the fact that how companies acquire customers — and, what types of customers they acquire — is one of the biggest driving factors of retention. Customers who are acquired purely based on promotion are, generally speaking, more likely to churn.

“I think that is the biggest driver of retention, ultimately, is, what are the expectations that you’re setting?” Dolwani said.

What I’m reading

- Preppy streetwear brand Rowing Blazers has been acquired by Burch Creative Capital.

- Supergoop has a new CEO. Lisa Sequino, formerly the CEO of JLo Beauty, is taking over the top job at the popular sunscreen brand.

- Interior design services startup Havenly is on an acquisition spree, snapping up other startups in the home goods and furniture space. The company recently acquired DTC home decor brand The Citizenry, which is the third startup Havenly has acquired in the last two years.

What we’ve covered

- How brands like Claire’s and Bubble are trying to woo Gen Alpha influencers.

- Piercing startup Rowan unveils plans to double its store count this year, and hopes to end 2024 with more than 60 brick-and-mortar locations.

- As venture capital funds pull back on consumer, more private equity firms look to play a bigger role in startup investing.