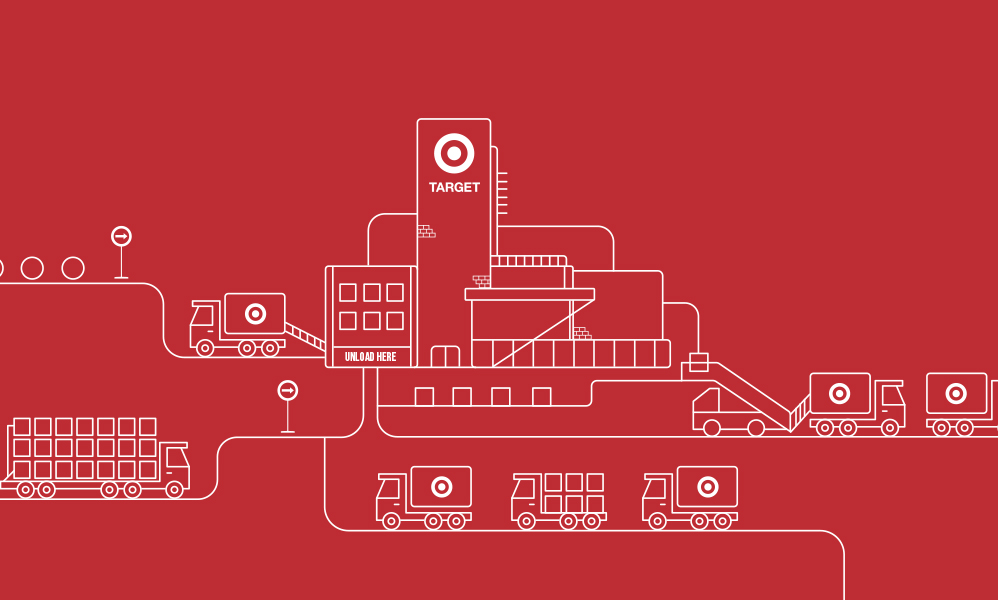

Target is looking beyond its stores to make the last mile of delivery more efficient

For the past several years, Target has centered its e-commerce strategy around using its stores to fulfill online orders. And while that has proven to be more cost-effective, the model also has its limitations.

Now, Target is starting to look beyond its stores to more efficiently fulfill online orders. The company announced last Thursday that it is testing out a new delivery process in Minneapolis. Online orders will still be fulfilled by workers in stores. But, Target will send packages to a sortation center the company built last year, where they will be sorted into batches by neighborhood, using technology Target acquired from a startup called Deliv last year. That way, workers from Shipt, another same-day delivery service Target acquired in 2017, can more easily make multiple deliveries at once.

One of the evergreen challenges that retailers have yet to solve for is how to make the last mile of delivery more efficient. And it’s a challenge that’s only gotten more urgent as e-commerce sales ballooned last year — Target, for example reported that digital comparable sales were up 145% between 2019 and 2020. Target’s approach follows in the footsteps of other retailers like Best Buy, Amazon and Walmart. Fulfilling online orders more efficiently, particularly in dense areas, relies on some combination of relying on the company’s stores to fulfill orders, and building out separate facilities that use automation to better sort packages. All retailers are still trying to figure out what the right combination is.

“Just physically shortening the distance that the package has to travel can reduce the speed of fulfillment in a way that is a bit more cost effective, so retailers are building out their own frameworks and infrastructure for doing that,” said Sarah Marzano, senior principal analyst for retail at Gartner.

The rush to turn stores into fulfillment centers, Marzano said, has been lead first and foremost by retailers trying to match Amazon’s one-or-two day delivery speed most cost effectively. And for a retailer that has thousands of stores located across the country, historically, there’s been a good chance that those stores are located more closely to customers than an Amazon warehouse.

Target disclosed during its fourth quarter earnings that 95% of its orders were fulfilled by stores. By relying on its stores to fulfill orders, Target hasn’t had to spend money building out more warehouses. But, Target has had to make some other capital expenditure investments to support this model. The company has remodeled most of its 1,868 stores, renovating about 300 per year since 2017, in order to build out more backroom space so that workers can fulfill more online orders.

But, as Target’s most recent announcement shows, relying solely on stores to fulfill online orders has its limitations — namely, that it takes up a lot of space. And the company is exploring whether it’s more efficient to sort packages in a separate facility.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

“As [fulfilling online orders] becomes more and more of your store’s volume, the shopping experience becomes less optimized for people that are actually shopping the store,” said Bryan Gildenberg, svp of commerce at Omnicom Consulting.

Finding the right fulfillment model

Other big-box retailers and grocers, are also exploring similar, though not exact, approaches. In grocery, for example, Albertson’s for example is testing out microfulfillment centers, which are smaller fulfillment centers attached to existing stores, but are better suited for fulfilling online orders. Albertson’s has built two facilities — run 10,000 to 15,000 square feet and only carry the top-selling products in that area — thus far, in partnership with Takeoff Technologies.

Another approach that’s being explored, particularly in grocery, is to create dark stores, which again are built solely for fulfilling online orders. Amazon’s Whole Foods is testing this out, having launched a dark store in Brooklyn in September.

Meanwhile, big-box retailers, like Target, are mostly looking at how they can fulfill online orders most efficiently by remodeling their existing stores. Best Buy said last August that it would be remodeling 250 of its stores to serve as “fulfillment hubs.” Though Best Buy ships out orders from all of its stores, it is remodeling all of these stores to handle significantly more volume.

Walmart, recently began testing what it calls “market fulfillment” centers, which are mini-fulfillment centers attached to or located within the store, depending on the store’s layout. Walmart first tested out this type of fulfillment center at a New Hampshire store in 2019, and then said in January that it would be expanding this type of fulfillment center to an undisclosed number of stores. As of last May, Walmart said that it now ships out online orders from 2,500 of its 4,3743 U.S. stores.

The question all of these companies face is just how high of a volume of online orders its stores can handle. And whether — even after they’ve remodeled locations — retailers find they still have to built additional dark stores or sortation centers in dense regions, as Target is doing.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

“What I expect to see is retailers continuing to think really thoughtfully about how to use their existing physical store infrastructure and investments — how can you make your stores work harder for you?” said Marzano.